My 17-day career in the Air Force being over (see April 20), Peggy and I returned to Mississippi where I got a job as a fifth grade teacher in Brookhaven, my hometown. The year was 1973, and Fannie Mullins had been a segregated black school until a few years earlier, so it was in

Little Egypt a part of town that few white people had previously visited. The neighborhood was poor, and the streets were narrow and lacked curbs or sidewalks.

The principal (Dow) and three of the other teachers (Tillman, Brown, and Goodwin) were black men, making me the only white male. They greeted me coolly, but without hostility. Goodwin even invited me to go fishing one afternoon. I didn’t fish, but then I didn’t figure that the invitation was really about fishing anyway. I figured it was really about seeing whether I was openly bigoted. When I passed the test, no other invitations were offered. The truth was that the other men at Fannie Mullins didn’t want to socialize with me anymore than I wanted to socialize with them. We simply didn’t have much in common.

People from outside the South tend to see everything that happens there in terms of race, but things aren’t that simple because, in the modern South, cultural differences are probably more important than racial ones. Let me give you an example that might sound familiar. Compare an ordinary black church to an ordinary white church of the same denomination. The dress, the music, and the preaching style are quite different, but are these racial differences, cultural differences or a combination? How would you even know?

I’ve been to scores of teachers’ meetings during which the white teachers sat together on one side of the auditorium, and the black teachers on the other. Sometimes, a teacher might cross over, and I was never aware that anyone had a problem with it; but the fact is that the white teachers weren’t excluding the black teachers (or vice versa), but that everyone was exercising his freedom to sit where he pleased. Maybe this is hard for white people from other places to accept because they know very few black people, and the black people they do know fit into the dominant white culture. But Mississippi is roughly half black (more in places), and this enables two distinct cultures to exist side by side.

The other men at Fannie Mullins wore ties and sometimes sports coats if not full suits; I didn’t. One day, Mr. Dow ordered me to at least wear a tie, so I starting wearing a clip-on to work, only to take it off as soon as I got to my room, and not put it on again until I took my class to lunch. He gave me grief about this from time to time, but I hated ties; I didn’t see the sense in them; and I sure as hell wasn’t go to wear one in a Mississippi school that didn’t have air conditioning.

The third year I taught, a new roof was put on the flat school building, and the tar for the project was melted right outside my window over a period of weeks. This created such a smoky stench that I had to keep the windows shut, and between the smoke and the 100 degree plus temperatures, conditions were almost unbearable. No one learned in my classroom; they simply survived. When I complained, Mr. Dow said that he had ordered the cooker to be placed outside my room because I was a man, implying, I suppose, that this made me better qualified to suffer. I didn’t think it prudent to mention that there were other men he could have chosen, but we got into a bit of a row anyway. One thing led to another, and he ended up giving me hell about the tie issue. “Why can’t you just follow my orders like the other men?” he asked. I said it was because I wasn’t afraid of him like the other men (Dow was big and gruff). The other men had hardly confided in me, so I couldn’t be sure that this was true, but I was pleased to see that it very nearly made him apoplectic.

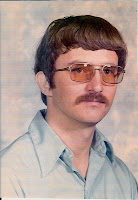

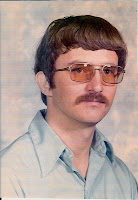

I finished my third year as a teacher in 1976. I had wanted to grow a beard for months, but put it off until summer. I was actually naïve enough to think my beard wouldn’t be a problem when school started back in late August. My reasoning was that three of the four remaining men (Goodwin had died) had moustaches, and so I wasn’t introducing facial hair, I was simply extending its range. I went to the school a few days before classes started to get my room set-up, and in less than five minutes Mr. Dow was on the intercom ordering me to his office. I knew from experience that this boded no good.

“Snow,” he said (of course he really used my other name), “I see that you grew a beard over the summer, and I want you to know that it looks mighty fine, but I’m assuming you’ll be shaving it off before school starts.”

“No, sir, I hadn’t planned to.”

“Well, I just don’t know if Mr. Trammel [the area superintendent] will let you teach looking like that.”

“Well, sir, I don’t intend to shave.”

I went back to my room and waited to see what would happen next. A few minutes later, he summoned me back to his office, and said that Mr. Brumfield wanted me to call his secretary and make an appointment to see him. Mr. Brumfield was the assistant superintendent. Both he and Mr. Trammel had been working their way up the career ladder when I was a kid, and this meant that they both had occasion to spank me from time to time for fighting.

Mr. Brumfield had no better luck getting me to shave than had Mr. Dow, so he passed me along to Mr. Trammel who found me equally recalcitrant. As my superiors saw it, their main weapon was to threaten my advancement into an administrative position. Little did they know—and scarcely could they believe—that I didn’t want to advance. They then threatened to take away my students and leave me in an empty classroom all year. The image of being paid to sit around and read sounded as appealing as it did unlikely, so I offered no protest about that either. Finally, they said that I was a disappointment to them, an embarrassment to the Brookhaven Municipal Separate School District, and intimated that I might be fired. This option was also appealing because I had by now talked to someone from the ACLU, and was pretty sure I would win if we went to court.

Why did they object to your beard?Most white Southerners in 1976 associated beards with dope-smoking hippies (which wasn’t far off the mark in my case). I assumed that black people felt the same way, so I was surprised to learn that they associated beards, not with peaceful hippies, but with violent militants. Even so, no one in the administration ever admitted that he personally had an issue with my beard; they were simply concerned about what the community at large would think.

School started without anything more being done. I waited. Weeks passed. I finally realized that nothing was going to be done. My superiors would probably hate me and maybe even look for an excuse to get rid of me, but they had no doubt seen their lawyer and decided that it wouldn’t be cost effective to go to war over a beard.

Meanwhile, I struggled within myself over whether to shave in order to placate them. The consensus among people who I talked to was that the job was more important than the beard. Yet, I knew that if I shaved, I would become so resentful that I would probably quit the job anyway. I turned to nature, marijuana and Thoreau—all at the same time. Everyday after work, I would retreat to the woods with a joint and my compendium of Thoreau.

I saw a lot of Mr. Dow that year because he was forever on the intercom, summoning me to his office to give me hell about one thing or another. He even said that parents complained more about me than they did about all his other teachers combined. I doubted this because I had never been told of a single complaint in previous years and only one specific complaint after I grew my beard (someone objected to the relaxation exercises that I gave the kids on the grounds that they were un-Christian). Indeed, I had always been popular with students and parents so far as I was aware.

The year passed and contract renewal time came around again. I didn’t sign on for another year for various reasons. The hostility of my superiors was one of them, but just as important was a reason that makes no sense to most people. Contracts make me claustrophobic. Even though I had every intention of seeing the job through, the knowledge that I had to sign a paper promising to be in a certain place at a certain time on a certain day months and months in advance gave me the willies. Now that things were especially tense at work, the prospect of signing a contract weighed on me even more heavily.

Were you a good teacher?Not especially. I liked the kids, and the kids liked me because I was creative in my teaching and my assignments, and because I made them laugh. The problem was that I didn’t take my responsibility seriously. I taught 150 kids a day, 30 at a time for 50 minutes at a time, and although I wanted to help the underachievers realize their potential—no one had helped me, and I failed three grades—I felt powerless to make a difference. And, as with every other job I ever had, I hated taking orders; I felt underpaid; and I thought I deserved a job better suited to my genius. Unfortunately, I never figured out exactly

what job was better suited to my genius or even where my genius lay. I just knew that I had a sense of destiny, a feeling that I was meant for greatness, but I lacked any sense that I had to work for it. I believed that if I waited long enough, the universe would drop success into my lap.

Another major problem that I had was shyness. I simply couldn’t pull off speaking to groups of adults, and I was even afraid to speak to my students’ parents at open house nights or during conferences. I cannot overstate the severity of this problem. I can but report that I overcame it around my fiftieth year. If I had been able to overcome it decades sooner, it would have opened doors that were completely closed to me. For example, I might have gotten an advanced degree and become a professor.

If you were so shy, how were you able to stand up to people who opposed you?I was also principled and stubborn. If I thought someone—or some group—was trying to run over me, I could find the strength to resist simply because I feared being unable to live with myself if I knuckled under. I remember but one occasion when I let someone intimidate me, and I tortured myself over it for many years.

I saw this same resistance in my father who was even shyer than I. His voice would break simply from trying to order food in a restaurant, but if he was mad enough, he could fill a football stadium with profanity. His problem was that his anger was consistently misplaced and misused. I have made a valiant effort to correct that in my own life, and as a result, I seldom lose my temper.

I was too immature to be a good teacher. Yet, if I were teaching today and the beard issue came up, I would struggle with it now just as I struggled with it then. Would I give in to the silly rules of silly men who valued conformity and public relations over freedom and education, or would I deprive my students of a good teacher—and I think I have it in me to be a good teacher? My choice is not immediately obvious. Here is what Thoreau wrote about his experience. At the time I taught, it mirrored my own.

“I have thoroughly tried schoolkeeping and found that my expenses were in proportion, or rather out of proportion, to my income, for I was obliged to dress and train, not to say think and believe, accordingly, and I lost my time into the bargain. As I did not teach for the good of my fellow-men, but simply for a livelihood, this was a failure.”

Part 1

Part 1