|

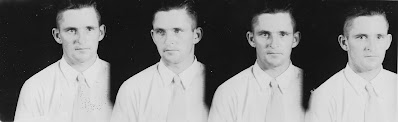

| Tommy 1909-1994 |

When I was in my twenties, my father and I were installing office cubicles in the showroom of an empty car dealership when he fell from a ten-foot ladder and knocked himself out on the concrete floor. I called an ambulance and my mother, Kathryn, who beat the ambulance to the hospital. When the doctor decided to admit my still unconscious father, a nurse ordered Kathryn and me from the room so she could undress him. Kathryn objected that Tommy was “a very private man who would want his family to undress him.” When the nurse demurred, Kathryn ordered her from the room. Beneath his khaki shirt and striped overalls, my father wore a bra, a slip, and panties. Kathryn made no comment, and I asked no questions.

When he returned to work, Tommy told me that he was a woman in a man’s body. Little boys wore dresses when he was a child, and when the day came that his mother, Fannie, said he was old enough to wear pants, Tommy refused. His mother was accepting of the fact that her son wasn’t like other boys, but she couldn’t allow him to violate the wishes of society and her preacher-husband. When Fannie was 85, she broke her hip. Tommy said to her, “Don’t worry, Miss Fannie, you’re going to be fine,” and she replied, “I don’t think so, Tommy.” When I didn’t cry at her funeral, Tommy praised me for “being a man about her death.”

Before he and Kathryn married in 1948, Tommy had a reputation for getting into fights, although he never hit a woman or a child. The nearest he came was on a Sunday morning when, at age four, I crawled under the bed after he scolded me. He said that if I didn’t come out, he would drag me out and spank me, so I came out. Not having the heart to discipline his children, Tommy tacitly put Kathryn in charge of disciplining me and my sister, Gay, and we ignored her, especially after we reached adolescence.

|

| Bryd, Tommy, Edward, Fannie, Annabel, 1917 |

When Tommy’s father, Edward, was in a bad mood, he would sometimes whip Tommy’s older brother, Byrd, as the three of them worked in the fields. When the day came that Edward decided to beat Tommy, Tommy threatened to kill him, and Edward backed-off. In trying to understand how a child could so intimidate his father, I reflected upon the fact that Tommy always did what he said he would do, and that his shyness and soft-spokenness made him seem demonic when he shouted and cursed in anger. Because of him, I still react so strongly to voices raised in anger that I sometimes withdraw for days when Peggy yells at me.

When he was fourteen, Tommy beat someone for tripping him on the schoolhouse steps. The teacher spanked the other boy, but when he prepared to spank Tommy, Tommy pulled a knife. That night, the teacher came to his house and told Edward that Tommy would be expelled if he didn’t submit to being spanked. Tommy then moved to Galveston, Texas, where he lived with his older brother, Pat, and became a roofer.

After serving in the Merchant Marines during World War II (he was twice sunk by U-Boats), Tommy moved to New Orleans where he made friends with women who enjoyed selecting women’s clothes for him and watching him try them on. He also started having sex with men in mixed gender settings. In 1947, he moved to Route 4, Bogue Chitto, Mississippi, to care for his elderly parents and work as a building contractor. It was when he was remodeling a house for the Ernie Boone family that he met 33-year-old Kathryn, who was widow to Ernie’s brother, Dustin.

After Dustin’s death in 1942, Kathryn worked as a draftsman in the Orange, Texas shipyard, while shuttling her daughter, Anne, and her son, Jim Billy, between local families and the Methodist Orphanage. At war’s end, she took a job with Sears Roebuck and rose to the position of department manager. When Sears announced the opening of a new store in Jackson, Mississippi, Kathryn offered to transfer, partly because she was from Mississippi, but more importantly because Ernie and his wife, Nonnie, lived close enough that they could care for Anne during the week (Jim Billy stayed behind with Ernie’s sister, Bessie), and she could take the sixty-mile bus ride to see her on weekends. She desperately wanted to live with her children, but she would need to marry to afford it, and the fact that she was 33-year-old with two children left her with little hope. Then she met Tommy.

| ||

| Tommy and Kathryn at Ernie’s, 1948 |

Kathryn and Tommy dated on weekends and corresponded during the week. After two weeks, they were engaged, and while his letters gushed with adoration, hers were a mixture of romance and personal news. When she asked him to tell her frankly if his affection lagged behind her own, he assured her that it did not, and they proceeded to write more days than not during their three month courtship. After the first two weeks they were engaged with the certainty that happiness lay in the arms of one another. Tommy had yet to meet eight-year-old Jim Billy (who was still with his Aunt Bessie in Port Arthur, Texas), but he saw a lot of eleven-year-old Anne whom he called “our daughter.” He encouraged Kathryn to include her on dates and said he couldn’t love her more if he were her father.

Their engagement was greeted with stern disapproval on the part of Ernie, Nonnie, and Ernie’s four living siblings, all of whom questioned Tommy’s fitness to parent Dustin’s children. They might have looked askance at any man who threatened their control, but in trying to understand their hostility to Tommy in particular, I can only describe the Tommy whom I knew a few years later when his behavior might have become more extreme, as it continued to do.

On the positive side, Tommy was honest, debt-free, kept his word, didn’t drink, and was skilled in what he called “the building field.” On the negative side, he was paranoid, intolerant, easily angered, had been a brawler, and was believed to have been married three times (I’ve only found record of one marriage). Then there were his tantrums. Even something so trifling as splitting a board, misplacing a tool, or bending a nail could bring on repetitions of a litany of profanity: “Goddamn, the goddamn, mother fucking, goddamn, son of a bitching, goddamn nail to hell, GODDAMN IT!” He would work himself into such a rage that he would tremble and choke on his words. In his relationships with others, Tommy lived in the center of a figurative minefield that caused many to avoid him. Until Peggy’s arrival, I was the only person with whom he could harmoniously spend large amounts of time, yet even I often found it hard. When I said to him, “How do you expect me to respect you when you act like that?” he responded, “Fuck you! I don’t respect myself.”

In the months following their February 8, 1948, wedding, Tommy concluded that Kathryn had trapped him into marriage, presumably to provide a home for her children. I consider her incapable of such subterfuge, and I think the hostility of Dustin’s siblings was partly responsible for causing an already paranoid man to jump to the worst possible conclusion about his wife’s behavior. Additional marital stresses were caused by things that each had kept hidden during their brief courtship. On Tommy’s side was his belief that he was a woman; on Kathryn’s was her germophobia. (When her children kissed her, she would turn her face from them and say, “Don’t breathe on me,” while waving her hand to “fan the germs away,” and when I was a toddler, she would scoop me up and carry me indoors when buzzards flew overhead, so I wouldn’t be bombarded by germs.)

| |

| Gay, age 20 |

Given her germophobia, Kathryn must have been all the more upset by Tommy’s growing indifference to personal cleanliness. When I worked with him, he would sometimes arrive in the same filthy, sweat-drenched khaki shirt and striped overalls that he had worn the previous day, yet he was so oblivious to the fact that this led people to avoid him that he boasted of his hygiene.

That Kathryn was equally blind to her own inconsistencies was evident in her ridicule of Robert, the teenage son of her best friend. His effeminacy was bad enough in her view, but what made him truly ridiculous was his habit of draping handkerchiefs over doorknobs before turning them.

Several months into their marriage, Tommy and Kathryn were ready to move Anne and Jim Billy into their home. The night before this was to happen, Ernie’s sister, Bessie, kidnapped eight-year-old Jim Billy from Ernie’s house and drove him to her home in Port Arthur, Texas. Meanwhile, Ernie’s wife, Nonnie, instructed eleven-year-old Anne to refuse to go with Tommy and Kathryn. Upon seeing what was supposed to be the happiest day of her life transformed into a nightmare, Kathryn sobbed in devastation and Tommy trembled in fury. She later blamed her loss of Jim Billy on her former inlaws, but she lay the blame for her loss of Anne entirely on Anne. Later...

Tommy didn’t demand that Kathryn give up her job and their “cute little house in Jackson,” to care for his parents in their unpainted shack at Route 4, Bogue Chitto, but because she was a compassionate woman who yearned to recapture her husband’s love, she did. The shack had an outhouse for a toilet; kerosene lamps for lighting; a wood-stove for cooking; and a well-bucket for water. Most of her new neighbors were farmers, some of whom used mules for plowing and transportation.

Kathryn pleaded with Tommy to at least put a pump in the well and build her a proper bathroom, but his father, Edward, objected that he didn’t “trust electricity” and that it was “unsanitary” to eat and shit in the same building. When neighboring women in sunbonnets and flour-sack dresses observed Kathryn in her stylish shorts and blouses, they called her “Tommy’s city woman,” and they also ridiculed her because she was previously married, a head taller than they, and too thin for manual labor.

When Tommy failed to earn enough money as a carpenter to support his wife and parents, he built a store in their front yard and then returned to work, leaving her to run the store while also serving as the family’s cook, housekeeper, and caregiver for senile Edward, blind Fannie, and me—her new baby. When the store burned to the ground, Tommy blamed an unknown arsonist and took up farming. When that didn’t work out, he opened another country store that was practically adjacent to his brother Byrd’s large and well-established one. When that too failed, he returned to working as a carpenter/handyman, this time for Gerald Kees whose holdings included a Buick dealership along with commercial and residential property. The 55-hour a week job didn’t pay much, but Tommy’s growing list of financial failures had so rattled Kathryn—who had spent her life in dire financial straits—that she begged him to work for Kees rather than leave what he called “the sorriest state in the Union” and move to Louisiana in the hope of a better salary. This gave him yet another complaint to spend the rest of his life blaming her for.

Edward died in 1953, when I was four, and in 1959, Tommy moved his family into a rental house in nearby Brookhaven (population 11,000). Kathryn took a refresher course in typing and shorthand and did secretarial work at home. After Fannie’s death in 1961, Tommy built his family a spacious house three miles north of Brookhaven. In 1963, he suffered an undiagnosed back problem that left him hobbling about for a few years. He and Kathryn then opened a third country store, this one in their garage. After Tommy was well enough to return to work, Kathryn ran the store alone.

Tommy and Kathryn never denied me anything they could afford, and they never discussed their financial problems in my presence. Starting at age fourteen, I took a succession of part-time jobs (stores, funeral homes, paper routes, and ambulance services). I never gave a penny of my earnings to my parents, and they never asked my younger sister, Gay, or me to do chores. My father’s explanation was that he didn’t want his kids to have to work hard like he had worked. My mother never gave an explanation, but she surely knew that we wouldn’t have obeyed her anyway.

Tension at home often made life hellish, especially at mealtimes where variations on the following script were frequent. Tommy would smack his lips, eat with his mouth open, and loudly scrape his plate with his fork. These things so annoyed Kathryn that she would take her food to the far side of the room. This, in turn, so angered Tommy that he would say, “A pig wouldn’t eat this slop,” although her meal of cornbread, fried okra, iced tea, pork chops (or fried chicken), boiled limas with chunks of fat, white rice with gravy, and lemon pie, was identical to what women all over the South served.

Kathryn would then—in seeming innocence—say something to further enrage Tommy, who would up the ante by calling her a whore for bettering her living situation by luring him into a sexless marriage. As silent tears began to fall into Kathryn’s food, Gay was working herself into full-blown hysteria. Tommy would then turn his anger on Gay, “If you don’t dry up, I’ll give you something to cry about.” Meanwhile, Kathryn was blaming me “for keeping the poor little thing too upset to eat,” although I so disliked Gay that I hadn’t even looked at her. Tommy would then stalk silently from the room in one direction while Gay ran screaming in the other, slamming every door she came to even if she had to open it first. I, too, would leave, whether to mope in my room, buy some gin (until the Mississippi repealed prohibition in 1968, any kid could buy liquor), kill something with my .12 gauge, or throw my bayonet into a tree while pretending it was a teacher’s back.

Gay thinks our parents loved me more than they loved her, and she might be right because while I was silently dysfunctional, she threw tantrums, kept my shins black and blue by kicking them, looked like an escapee from a Nazi camp, and got pregnant by person-unknown, requiring a budget-busting trip to Denver for an abortion on the very day of my college graduation. Gay’s tantrums completely rattled Tommy whose nerves were none too steady anyway, and the fact that he and I often worked together further separated them. Kathryn devoted hours a week to begging Gay to eat and to give up smoking, but all she got for her efforts was Gay’s hatred.

I laughed at her attempts to discipline me, and Tommy didn’t discipline me at all, so I failed the sixth, the ninth, and the tenth grades, and often drove home drunk on weekends. I had been warmed by Kathryn’s love during prepubescence, but with the first signs of approaching manhood, her affection had turned to disgust. Not a day passed but what she would say, “Boy, I don’t know what’s gotten into you;” “Boy, I raised you to behave better than this;” and, “Boy, you will never amount to anything.” Because I concurred with her belief that I was stupid, I couldn’t argue. Despite years of summer school, I never graduated, although I accumulated enough credits to be admitted to a small Methodist college, an option that I found infinitely more appealing than a Vietcong landmine.

|

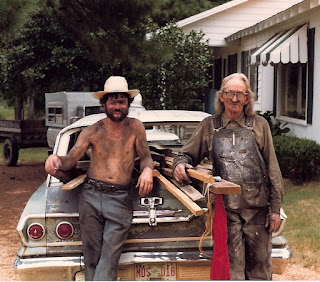

| Tommy and me after removing a plaster ceiling, 1980* |

By the time I met Peggy—at a Southern Baptist college—I had stopped listening to Kathryn’s insults, but Peggy certainly did, and they turned her against Kathryn. For her part, Kathryn called Peggy my “better half” and meant it, just as she meant it when she said, “Peggy is your meal ticket” (Peggy earned more than I), and, “Peggy deserves a better man than you.” Tommy adored Peggy from the day they met, but she held both my parents at a distance, calling them called Mr. ___ and Mrs. ___ until the day they died.

Gay later renounced our parents altogether in favor of calling her second husband’s parents Mom and Dad. They in turn bequeathed her tens of thousands of dollars that she spent on men and drugs—she twice awakened to find that the man she had gone to bed with was dead. After years of watching her use, abuse, and abandon people who made the mistake of loving her, I gave up looking for the good in Gay, who is is now dying of COPD and losing her vision to macular degeneration, which I also have.

After learning of her diagnosis, I

emailed her because I thought it was what a compassionate person should do, and I try to be a compassionate person. Because her feelings for me are as jaundiced as are mine for her, I didn’t expect a response, but she wrote, occasionally requesting money. Had I acceded to her requests, we might still be in touch. Gay’s existence

in my life used to be like a thick fog that would occasionally lift, allowing me to see the loving, playful, innocent, and elfin spirit that she used to be. That fog has not lifted in decades, and I doubt that I could recall more than a few hours of

happiness in all the years I’ve known her. Here are a few treasured memories...

Lying in my bed and listening to her sing herself to

sleep in the next room; watching her serve tea to an imaginary friend; seeing the glow in her face as she watched her favorite cartoon show, Rocky and Bullwinkle, on Saturday mornings; a birthday card that pictured a squirrel cracking a nut on the front and these words by her on the inside: “To a nut from a nut.” Finally, there was her buoyant search for islands of happiness within the ocean of her parents’ misery.

Despite my problems with my mother, I grieved intensely for 18-months after her 1988 death. My bad memories of her are outweighed by her love of plants; her enjoyment of Dylan Thomas; the litters of abandoned puppies that Tommy regularly brought home from the dump and that she fed around the clock with a baby bottle; the intellectualism she aimed for but never achieved; and her letters to the local newspaper in support of centrist causes and Democratic candidates. I suffered terribly from pleurisy as a child, and I also have fond memories of her rubbing my chest with Vicks VapoRub. Although the grease made me feel dirty, and the sharp pains in my chest were exacerbated by the cigarettes she smoked while applying the Vicks, I needed her affection so desperately that I even submitted to castor oil and enemas well into my teen years. My most cherished memory is of the two of us sitting in her wing-backed chair while watching her favorite TV show, Have Gun Will Travel, the main character of which was portrayed as an intellectual.

Of the three people among whom I grew to adulthood, it is Tommy who I love with an intensity that exceeds any love I’ve known aside from my love for Peggy. But, if Tommy was as bad as I’ve said, why do I still grieve for him 29-years after his death? Many reasons... He worked untiringly to support his family; he never cheated his employer; he exposed those who did cheat his employer; he gave me every advantage he could afford; he and I were the best friends that either of us ever had; and he told me things that few fathers would share and few sons would want to hear. Although much of his behavior appeared to come from weakness, I hold to the thought that transgender people are prone to anxiety, depression, alienation, loneliness, substance abuse, and suicide, even with a support system. My father had no such support, plus he was poor, friendless, poorly educated, unloved by his wife, unappreciated by his children, and unaware that other transgender people existed until he was in his fifties and read a Life Magazine article about the first American to undergo gender reassignment surgery.

Tommy didn’t want Gay to know he was transgender (“she couldn’t handle it”), but I’ve told others over the decades. In the ‘80s and ‘90s many people didn’t know what the word meant (some equated it with transvestism) while those who did know were appalled that I would share such a secret that, in their view, was shameful and might even cast doubt upon my own sexual normalcy. I shared it anyway because while I was very much humiliated by his tantrums, I wasn’t in the least embarrassed by his transgenderism.

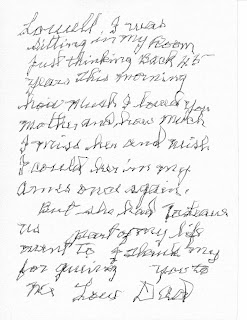

The only thing my father wanted from me was assurance of my love, and I could unhesitatingly say to him. “I love you with my whole heart, and what you’ve told me doesn’t matter.” Were he alive today, he might also ask that I affirm his womanhood, and that I couldn’t do. However, if forced to choose between lying and breaking my father’s heart, I hope I would have the virtue to lie, and the strength to live so that he wouldn’t question my honesty. On my 45th birthday, he wrote what proved to be the last words he set to paper. The room he spoke of was his bedroom in this house.

“Lowell I was sitting in my room just thinking back 45 years [ago] this morning how much I loved your mother and how much I miss her and wish I could [hold] her in my arms once again. But [when] she had to leave us, part of my life went to. I thank my [God] for giving you to me. Love Dad”

|

| Birthday card, March, 1994 |

Five months later, he died in the room in which he had written those words. I remembered his relationship with my mother very differently from how he did as death approached and he was again able to experience the consuming love he had expressed in scores of letters from the 1940s: “You cannot really understand my real feelings for anything that concerns you in any way for I love you so much, Darling, that it seems I cannot breathe without breathing your name for it means every hope and desire in life for me.” “When you are in my arms, you are just as much a part of me as my heart is because without you there would be nothing in life for me.”

I celebrate his forgetfulness of the hard years, just as I celebrate the fact that he was my father. He said that his years with Peggy and me were the happiest of his life, and I think it shows in the following photo which was taken when all that remained to him was to relax into the safety of our love and to know that his years of hard labor were over.

|

| Tommy, the summer before his death |

* A few years earlier, Tommy donned earrings, let his hair grow, and stopped running from the room when I visited so I wouldn’t see him in women’s clothing, Kathryn explained his long hair to others by saying that he thought it would make him strong like Samson.

Sources: (1) The memories of myself, my father, my mother, Peggy, Anne, and Gay. (2) My parents’ correspondence from October 28, 1947, to February 6, 1948. (4) The book Time is a Place by Anne Boone Johnson, Ph.D. (5) The book My 100-Year Journey by Mygnone Amazon Lenoir Boone with Anne Boone Johnson, Ph.D. (5) Ancestry.com