Democrats are too stupid to realize that gun control laws won’t work because criminals won’t obey them.

Gun violence is the price that a freedom-loving people pay for living in a free country.

Without guns, peace becomes impossible.

Despite having strict gun control laws, the people of Chicago and New York City shoot one another all the time. Clearly, gun control doesn’t work.

Guns aren’t the problem; guns are the solution.

Problems precede solutions, so if we didn’t have guns, finding a solution to gun violence would be impossible. What is the solution to school shootings?...

Arm every teacher, close every window, lower every blind, station armed guards at every door, install body scanners, x-ray backpacks, and use any and all other means to protect our children as long as those means don’t impinge upon the Constitutional right of every American to go through life armed-to-the-teeth in order to protect themselves.

Emotions are running too high right now to discuss gun control. We should wait until we’ve gone a year or two without a mass shooting.

If Democrats really cared about protecting children, they wouldn’t politicize the problem. This just goes to show what hypocrites they are.

America doesn’t have a gun problem; America has a mental health problem. This is why so many Americans are crazy.

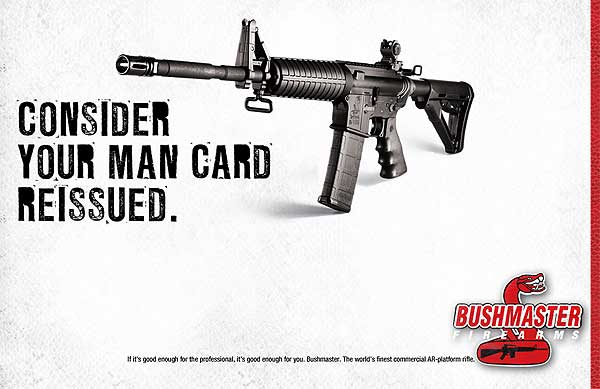

Remington plans to name its new high capacity assault rifle The Uvalde in honor of the children who died needlessly because their teachers weren’t armed. Gun manufacturers aren’t interested in making money but in selling good people guns so we can protect ourselves from the bad people they sell guns to.

Biden’s goal isn’t to protect our children, but to take away our guns so we can’t stop him from taking away our other freedoms. Democrats only voted for a man like that because they hate their country and want to destroy it.

I feel close to God when I send my thoughts and prayers to the victims and their families. I know that prayer works, and that God will protect the people I’m praying for. Their kids might be dead, but my prayers will at least keep the parents safe.

Teachers who are unwilling to shoot people who threaten their students should go to work for KFC or some other place that mass murderers don’t frequent.

God, not man, gave me the right to keep and bear arms. Giving up my guns would be like throwing God’s gift back in his face, and only a fool would throw things at God.

If Obama didn’t believe that guns protect people, he wouldn’t hide behind heavily armed bodyguards.

A lot of us Republicans are unwilling to pass laws to

save the lives of children, but if it was pregnant women who were being

murdered, that would be another matter because we care deeply about

fertilized eggs, embryos, and fetuses. It’s only after babies are born

that we lose interest, it being hard to love things that shit on themselves.

To summarize why I love guns in one word: Samuel L. Jackson.

Women need guns more than men because they’re the ones

who get raped. I’m a 73-year-old man, and if someone tried to rape me, I

would say, “Dude, are you blind!?”

God only helps those who help themselves, and he gave us guns for this purpose. Don’t ask for God’s help until you run out of bullets.

Every dumb-ass knows that fewer assault rifles would mean fewer dead children, but living guns are more useful than living children.

I saw an inspirational t-shirt at a gun show that read “A Lot of People Are Only Alive Because It Would Be Illegal to Shoot Them.” Graveyards would contain a lot more dead people if I could have legally shot every asshole who pissed me off.

The gun lobby speaks for me when it says, “I will only give up my gun when they pry my cold, dead finger from around its trigger.”

John Lennon speaks for me when he sings Happiness is a Warm Gun. Every time I hear that song, I remember that God always makes things happen for a reason, and the only reason he could have for making a man who was killed by a gun sing about how much he loved guns is that God loves guns.

Carrying a gun makes me feel I’m God because it gives me the power of life and death. For instance, I’ll be walking down the street smiling ear-to-ear because I’ll be thinking that if someone looks at me funny, I can shoot him dead right then and there because no matter how bad-ass he is, my .357 magnum makes me badder. That’s one hell of powerful feeling to have, so imagine how much more powerful that man in Vegas must have felt when he shot not just one person, and not just 100 people, but 500 people! Every time I replay the sound of his big old .50 cal, it gives me goosebumps because that’s how God sounds.

Foreign women drool and faint when they’re in the presence of an American man because they know that only men who carry guns are real men. Compared to American men, European men are like cardboard cut-outs that become flaccid in the rain. This is why European women would trade any fifty of their men for a single American man.

While it’s true that some children die after getting shot, the tough kids and the resilient kids walk away stronger for the experience. What’s more, every last one of them leaves the hospital knowing that if they had been carrying an assault rifle that day, the only corpse would have belonged to the bad guy.

I personally look forward to the day when a school shooting survivor stands up at an NRA convention and tells the world how important it is that every American twelve years old and older carry an assault rifle. Ukrainian kids do it, yet Ukrainian kids are sissies compared to American kids.

If you don’t love guns, then you can’t love children because God made them both. Satan made Democrats, and because Satan is a liar, Democrats are lying when they say they care about children.

If we made gun ownership mandatory, people would treat one another better because they would be afraid the other man might shoot them before they could shoot him.

If we banned guns, mass murderers would use bombs, which means that not only would more children be killed, the schools themselves would be destroyed. I’ve heard Democrats argue that if the students were all dead, the schools wouldn’t be needed, but they only say this because they’re too stupid to realize that empty schools could be turned into homes for the elderly.

I need guns to protect me and my family. Without a gun, what am I supposed to do when my second grader is being shot at—throw sardines?

Except for the ones who own guns, students, actors, teachers, and emergency room doctors have no business talking about gun control because they’re prejudiced. I knew a man who wouldn’t even take a shower without his .45. Now, that’s the kind of man who has something useful to say about gun control. The world would be better off if we all stayed in our lane instead of straying into other people’s lanes. Too many wrecks happen that way.

God couldn’t be everywhere, so he gave us guns. “Thank you, Lord, for sending your son to die on the cross so that the people of America can own all the guns we want. We commit our lives to serving you, the NRA, and Donald Trump. Let’s hear it now: USA! USA! USA!”

Even if we destroyed every gun on earth and made it impossible to replace them, people would still get shot, and their survivors would still need guns to keep other people from getting shot.

Guns don’t kill people; people kill people. Until I pick it up, my assault rifle is no more dangerous than the Easter Bunny, but after I pick it up, my neighbors run behind a concrete wall.

I’ve kept one loaded assault rifle on my coffee table and another beside my bed since 1989, and none of them guns has shot a single person. The only time that one of them even went off was when my wife forgot to engage the safety while dusting it. The only “person” killed was her piano, which was shot 24 times, but she didn’t play it anyway.

Crime goes down when gun ownership goes up because when there are millions of guns on the market, criminals don’t have to steal them. This is what’s called a reverse ratio.

Criminals are less likely to shoot at you if they know you’re carrying a gun. This is especially true if they can see that your gun holds more bullets than their gun.

Gun violence exists because bad people have too many guns and good people have too few guns. If we make gun ownership mandatory, bad people will be outgunned.

The Second Amendment to the Constitution gives me the right to buy all the guns I can afford and to carry all the guns my arms can hold.

The Uvalde shooter, like all mass murderers was a “transsexual leftist illegal alien.” (https://www.businessinsider.com/texas-shooting-uvalde-paul-gosar-touts-false-claim-transgender-woman-2022-5). Therefore, the goal shouldn’t be outlawing guns but imprisoning illegals, chicken-shit cowards, Hillary Clinton, and Democrats who run pedophile sex rings out of DC pizza parlors.

I have given you a lot of sound reasons for why I will shoot you dead if you try to take away my guns. If you still don’t see things my way, you’re either an idiot or a Communist, and I hope you rot in hell.

Finis

P.S. I’m going to be real with you now. If you think I made all this stuff up, visit the NRA website, listen to right-wing legislators, talk with gun loving family members, tune-in to conservative talk radio, and check-out gun rights newsgroups. No one does more to make the gun lobby look like a walking nightmare than the gun lobby itself. Just as the Republican Party has labeled the attempted violent takeover of the US government on January 6, “legitimate political discourse,”* it has been bought-and-paid-for by people who claim to be Christian, yet have no particular problem with children being so mutilated by exploding bullets that their faces are unrecognizable.** Despite their worship of Satan in the form of an assault rifle, these Republicans claim that their love for Christ gives them a monopoly on love and morality. Were it not so, the 268 mass shootings that have occurred in America as of June 1, might be hard to stomach.

*https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/04/us/politics/republicans-jan-6-cheney-censure.html

**https://theintercept.com/2022/05/26/ar-15-uvalde-school-shooting-vietnam-war/